Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm (AAA)

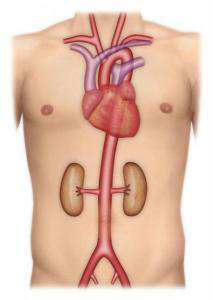

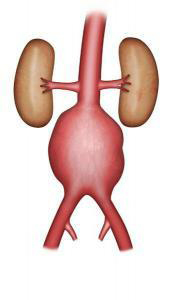

The aorta is one of the body’s main arteries. Starting at the heart, it goes down through the chest and abdomen, branching off into several smaller arteries that supply oxygen to the brain and various organs (Figure 1).An abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA) is a dilatation in the abdominal section of the aorta (Figure 2). The abdominal aorta has an average diameter of 18 mm in males. This diameter can vary by +/- 4 mm depending on gender and body fat. The term “aortic aneurysm” is used if the walls of the aorta are no longer parallel and begin to dilate. This bulge may be even and extend along most of the abdominal aorta (fusiform aneurysm), or it may be limited to one section (saccular aneurysm). Aneurysmal dilatation of the aorta causes turbulent blood flow, which in turn leads to the gradual formation of a thrombus (clot or coagulated blood) on the inner wall of the aneurysm sac. AAA growth is highly variable. Its diameter can stay stable for several years or, to the contrary, increase quickly and exponentially. It is therefore necessary to monitor the diameter of the aneurysm. The average growth is 4 per year for aneurysms 40 to 50 mm in size.

Figure 1: Normal anatomy of the aorta

Figure 2: Aortic aneurysm

Causes and affected populations

Aortic aneurysms are linked to the rarefaction of the elastic fibres in the artery wall. They most often affect men over age 60, and in rarer cases, women and younger subjects. Prevalence (frequency of the disease in the population) is 4-8% for men over age 60, and 1-3% for women, but trebles in the presence of associated cardiovascular risk factors (e.g. smoking, high blood pressure) or family history. The incidence (number of new cases each year) is 39/100,000. Atherosclerosis (the abnormal deposit of fatty plaque on the arterial wall) is the main cause of aneurysms. In some rarer cases, an aneurysm is caused by infection or inflammation.

Risks

The evolving risk is the rupture of the aneurysm, which is often fatal. This risk becomes considerable once the diameter exceeds 50 mm. Rupture most often occurs in the abdominal cavity, causing an often fatal massive haemorrhage. Sometimes the rupture is smaller and emergency surgery can be performed after transferring the patient to a vascular surgery clinic or ward.

Symptoms

Most often, AAAs do not produce any symptoms. Sometimes they are discovered during a medical examination involving abdominal palpation. They may be associated with abdominal or lumbar pain. If a known AAA larger than 40 mm in diameter is associated with abdominal or lumbar pain, an emergency CT scan and the opinion of a vascular surgical are required. When the aneurysm is small or the patient is overweight, it is not always easy to detect an AAA.It is most often discovered by accident during medical imaging for another condition: Doppler ultrasound screening for diseases of the lower limb arteries or veins; abdominal sonogram particularly for prostate conditions; or an abdominal or lumbar CT scan for diseases of the spinal column.

Main exams

An aortic sonogram is a simple exam used to diagnose the AAA and determine its size. An aortic CT scan provides more precise data on the aneurysm, its dimensions, and its extent.

Once an aneurysm has been detected, if its size does not warrant treatment, it should be monitored by ultrasound every six months or yearly. The choice of technique and frequency of monitoring will depend on the size and shape of the aneurysm.

Main treatments and their risks

AAA treatment requires medical care in a vascular surgery clinic or ward. To precisely assess the operating risk, preoperative exams are required: heart, kidney and lung screening, and a Doppler ultrasound of the carotid arteries. Based on these various exams and the age of the patient, the risk of treatment can be more accurately assessed.

The indication for treatment depends on the diameter and other morphological criteria of the aneurysm, as well as medical criteria relating to the patient’s age and state of health.Treatment is most often indicated once the diameter of the aneurysm is over 50 mm. The risk-benefit ratio of treatment must be assessed by comparing the risk of rupture to the operative risk. In some cases (e.g. a painful or fast-growing aneurysm; a young or female patient), indication may be discussed before the 50 mm threshold. In very elderly patients, or in cases where preoperative exams reveal the failure of one or several organs, it may be decided to continue monitoring aneurysms larger than 50 mm. The repair is performed after a preoperative meeting with the anaesthetist.

Two techniques to treat an AAA

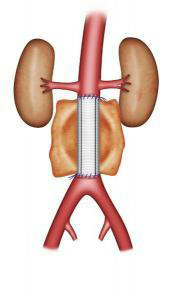

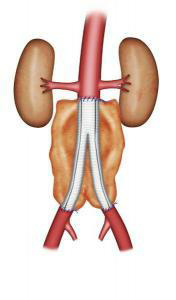

Open repair has been performed for several decades. This procedure requires a laparotomy under general anaesthesia (i.e. the abdomen is opened). The laparotomy is performed with a vertical or transverse incision on the abdomen, or with an incision on the left side of the body. The operation can sometimes be performed using laparoscopy (i.e. small incisions and a video camera). The surgeon replaces the aorta with a vascular graft, sewn with non-absorbable thread to the healthy section of the aorta above the aneurysm, and to the aorta or the iliac arteries below (Figure 3-4). This procedure varies in length, depending on the complexity of the surgery. Post-operative monitoring can require several days in an intermediate care unit.

The average hospital stay in eight days, but can vary depending on the patient’s condition prior to surgery and the postoperative outcomes.

Figure 3: Aortic graft

Figure 4: Aortic bi-iliac graft

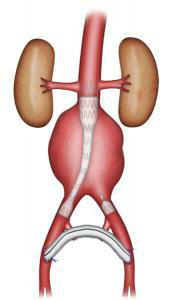

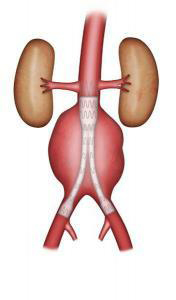

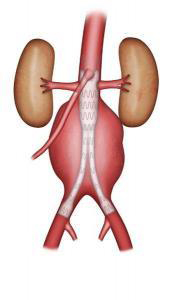

Endovascular repair involves excluding the aneurysm with an endograft (vascular prosthesis supported by a stent, an expanding metal mesh). The endograft is introduced through the femoral arteries in the groin (Figures 5-6). This type of repair may be suggested if a CT scan reveals very precise morphological criteria. The technique does not require opening the abdomen. The approach to the femoral arteries is either through a small incision in the groin, or by a percutaneous puncture with no incision. The duration of the operation is highly variable, depending on its technical complexity, while the length of hospitalisation depends on the operative outcome. It is usually shorter than for surgical treatment.

Figure 5: Uni-iliac stent graft

Figure 6: Bifurcated stent graft

Medical follow-up

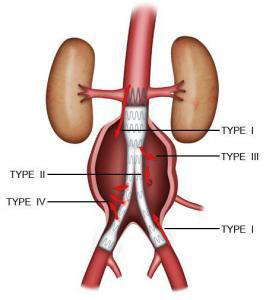

Open repair requires follow-up one to three months after the operation, then a regular Doppler ultrasound to ensure that the graft presents no anomalies and that there are no other aneurysms.Endovascular repair requires very strict, non-elective follow-up with CT scans or Doppler ultrasounds, to verify that the aneurysm is excluded and that there are no endoleaks.

Check-ups are done every six months for two years, and then once yearly. Some endoleaks are caused by an improper seal of the endograft, exposing the patient to the risk that the AAA will grow and consequently rupture. These require further treatment. Other endoleaks are slow and require no further treatment. In conclusion, there are several types of endoleaks of varying degrees of seriousness.

Find out more…

Etiology of AAA

The rarefaction of the elastic fibres of the aortic wall is believed to have several causes, such as a genetic defect or disrupted protease activity. Atherosclerosis promotes the development of these anomalies. The evolution of the AAA depends on Laplace’s law, which states that the force applied to the aortic wall is proportional to the arterial pressure and the radius (and therefore at the base of a vicious circle that tends to make the aneurysm grow).

Risk of rupture

The annual occurrence of ruptures is low when the diameter is inferior to 50 mm (less than 1% for diameters below 40 mm and 0.5 to 3% for diameters between 40 and 49 mm). The annual occurrence of ruptures is 3 to 10% if the AAA measures 50 to 60 mm in diameter, 10 to 20% for 60 to 69 mm and 20 to 40% for AAA over 70 mm in diameter. Factors that increase the risk of rupture are growth of over 10 mm per year, smoking, high blood pressure, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (a breathing disorder frequent in smokers), and the saccular shape. Finally, in aneurysms of equal diameter, rupture is three times more likely in women.

Additional exams

CT scans are crucial in preoperative aneurysm screening. They must explore the entire thoracic and abdominal aorta in order to detect a thoracic aortic aneurysm. If the diameter is less than 45 mm, one annual Doppler ultrasound is enough. But over 45 mm, it is preferable to screen every six months.

Risks of treatment

The most frequent postoperative complications affect the heart, breathing, kidneys, or digestion, or involve haemorrhaging or infection. Postoperative mortality averages 4-5% for conventional open surgery and 1-2% for endovascular repair. This better performance of endovascular repair in terms of short-term mortality drops if long-term postoperative mortality is considered. With endovascular repair, the risk of redo repair is larger.

Repair

In endovascular repair, the aneurysm is excluded using a bifurcated stent graft consisting of two branches for the iliac arteries or by an aorto-uni-iliac stent graft combined with a femoral-femoral bypass; the choice between these two is based on the morphological criteria detected by the CT scan. The main considerations are the length and diameter of the proximal neck (healthy segment of the aorta before the aneurysmal dilatation), the diameter of the iliac arteries, and iliac tortuosity. The graft sealed is produced by radial force. A new generation of endografts are under evaluation (fenestrated grafts) for use when the proximal neck is very short. These endografts feature fenestrations on their proximal end for the renal arteries and the superior mesenteric artery (branch of the aorta that supplies the intestine) so that the graft can be proximally anchored even if there is no proximal neck (Figure 7).

Figure 7: Fenestrated graft

Endoleaks :

When arterial flow leaks into the aneurysm sac outside the endograft, this is known as an endoleak. It means that the graft is not properly sealed. There are four types of endoleaks. Type I endoleaks are proximal or distal leaks caused by incomplete seal at the end of the graft. These are the most serious type of endoleak. They always require redo repair. Type II endoleaks are caused by backflow from the aorta’s collateral arteries (e.g. lumbar or inferior mesenteric arteries). They are monitored and only require treatment if the diameter of the aneurysm increases. Type III endoleaks are caused by a rupture in the endograft or an inadequate seal between overlapping graft joints. Type IV endoleaks are caused by the porosity of the graft fabric. The latter two endoleak types are very rare, and may require redo repair (Figure 8).

Figure 8: Types of endoleak