Defining carotid stenosis

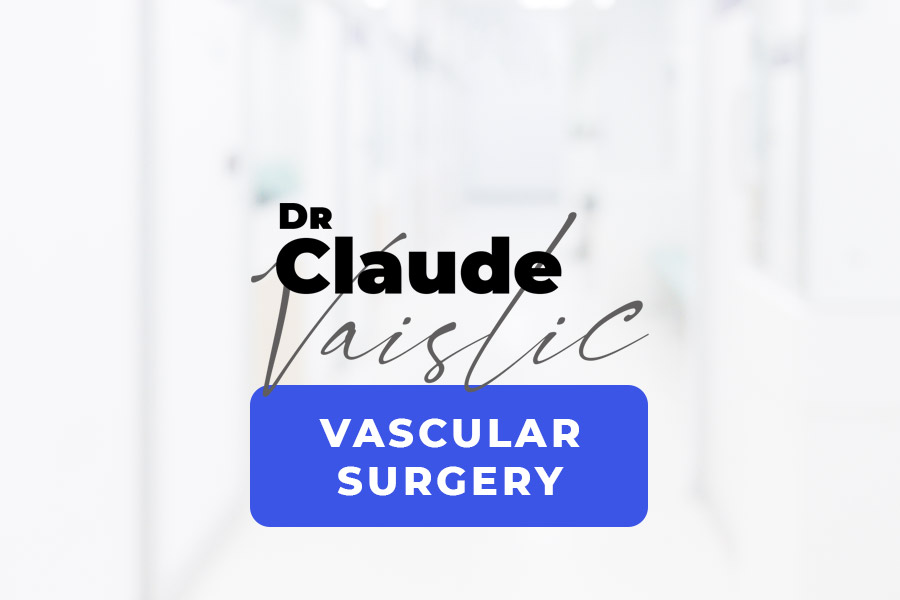

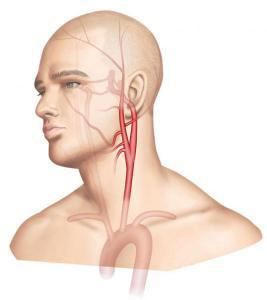

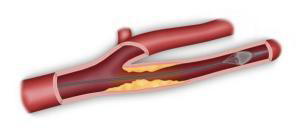

The internal carotid is an artery located in the neck (Figure 1). It extends upwards to the brain, supplying it with the oxygen it needs to function properly. The carotid artery is around 4 mm in diameter. It can become obstructed by atheromatous plaque (fatty build-up) on the artery wall. This leads to stenosis, a narrowing of the artery (Figure 2).

Figure 1 : Carotid anatomy

Figure 2: Carotid stenosis

Ischemic cerebrovascular accidents (ischemic strokes)

Ischemic cerebrovascular accidents occur when a part of the brain is deprived of oxygen. Amongst the many causes are thrombosis (obstruction) of the internal carotid artery or cerebral embolism (migration of a clot or debris from a fatty plaque) arising from carotid stenosis. In both cases, the blood supply to a part of the brain is disrupted, causing a neurological deficit (paralysis) of varying degree depending on the region of the brain affected. The paralysis may affect an entire side of the body (hemiplegia) or a part of the body (e.g. an arm or leg) and is occasionally associated with facial paralysis and/or speech problems. Paralysis occurs on the side of the body opposite that of the arterial lesion (i.e. a right hemiplegia results from a stenosis of the left carotid, and vice versa).

A stroke may be transitory (transitory ischemic attack, or “mini-stroke”) if the symptoms resolve within a few hours. Otherwise, the incident is termed a cerebrovascular accident. Recovery – partial or complete – takes several weeks. However, the damage is occasionally major and irreversible.

In some cases, vision is damaged due to central retinal artery occlusion (CRAO), causing temporary or permanent blindness. In this case, the affected eye is on the same side of the body as the carotid lesion.

In France, the annual incidence rate for strokes (number of new cases each year) is two per 1,000 (all ages combined), with 15-20% of deaths occurring within the first month following the stroke and 75% of surviving patients experiencing after-effects. Prevalence (the frequency with which the sickness is found in the population) is five per 1,000 (all ages combined). The average age for first stroke is 71 for men and 76 for women, however 25% of stroke victims are under age 65. Of these strokes, 25% are linked to atheromatous carotid lesions.

Causes and affected populations

Carotid stenosis is promoted by cardiovascular risk factors such as smoking and alcohol use, high cholesterol, high blood pressure, and diabetes. These risk factors encourage the formation of fatty streaks on the walls of the arteries, particularly in the internal carotid in the neck. These deposits form atheromatous plaque.

Risks

The evolving risk of carotid stenosis includes both thrombosis (occlusion) of the carotid and the formation of clots which may then break off and enter the brain. This occurrence is called an embolism, and results in the occlusion of an artery in the brain, bringing on neurological or eye problems.

Symptoms

Most often, mild carotid stenosis presents no symptoms. In these cases, the carotid stenosis is said to be “asymptomatic”. If a mini-stroke or stroke is linked to the carotid stenosis, it is then said to be symptomatic. Symptoms vary, depending on which area of the brain is affected.

Main exams

Doppler ultrasound is a simple, painless exam that helps us assess the seriousness of carotid stenosis by measuring the degree of narrowing in the artery. This measurement is very important since it will determine the course of action to take. If the stenosis is greater than 60% of the artery’s diameter, in most cases a CT angiogram, or in some, an angio MRI, will be prescribed to obtain a more precise analysis of the carotid stenosis. CT angiography or MR angiography will determine the degree of the carotid stenosis and analyse both the other arteries leading to the brain and the parenchyma of the brain, to assess the stenosis’ consequences on cerebral vascularization.

Main treatments and their risks

The choice of treatment depends on two main criteria: the degree of stenosis assessed, and whether or not it presents any symptoms. The indication for treatment may also depend on the shape and size of the atheromatous plaque as well as general criteria common to all surgery, such as age and cardiac or respiratory health. Treatment is chosen along with the vascular surgeon during an informed consent consultation outlining the various therapeutic possibilities.

Medical treatment

For all cases of carotid stenosis, medical treatment includes controlling cardiovascular risk factors and taking antiplatelets (to improve blood flow) and statins (to diminish blood cholesterol levels). The stenosis is then monitored by Doppler ultrasound every six to twelve months, depending on severity. If the stenosis is moderate, medical treatment combined with regular monitoring is sufficient.

Surgery

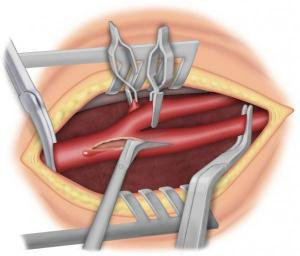

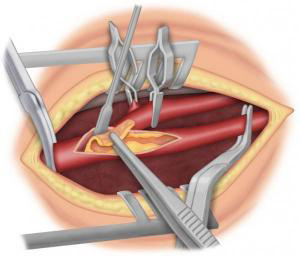

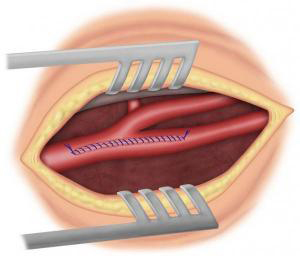

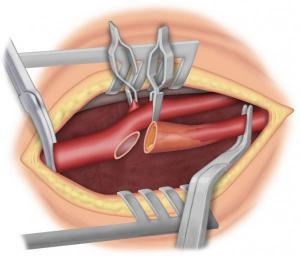

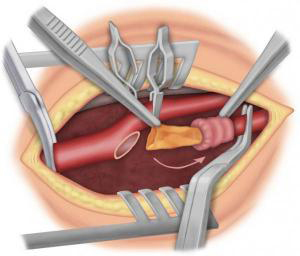

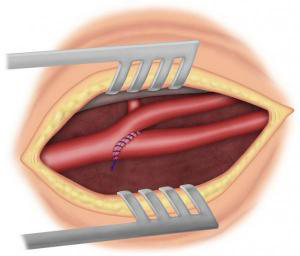

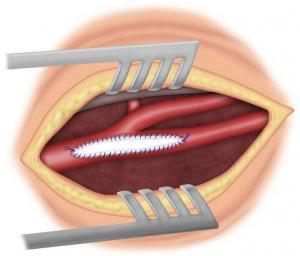

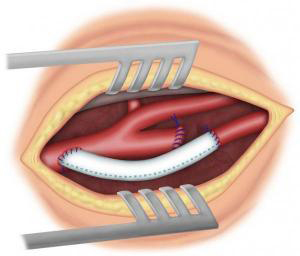

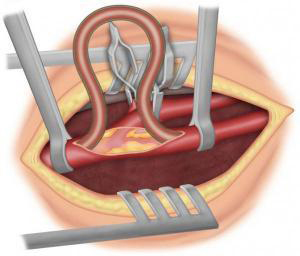

If the carotid stenosis is severe, the benchmark treatment is surgical removal of the atheromatous plaque. This procedure is known as a carotid endarterectomy (CEA). It can be performed under general or local anaesthesia (in the neck). After making a vertical incision in the neck, the surgeon opens the carotid to remove the atheromatous plaque (Figure 3-4). The surgeon then either directly sutures the artery (direct suture, eversion or eCEA) (Figure 5-6) or sutures a patch (Figure 7) to widen the artery. In some cases, an arterial bypass may be required (Figure 8). This operation lasts about one to two hours. To protect the brain, various techniques are used during the operation. The patient is then monitored in an intermediate care unit for 24 hours. The length of hospital stay varies depending on the care unit in question, the patient’s condition prior to surgery, and the postoperative outcomes. It averages four to six days.

Figure 6a

Complications are rare and have considerably dropped thanks to precautions taken before and during surgery. The most serious complications are cardiac and neurological, including the risk of mini-stroke or stroke. Complications arise in 2% of cases of carotid stenosis with no history of symptoms (asymptomatic stenoses) and 4% of cases with a history of symptoms (symptomatic stenoses). Other complications, in order of frequency, are hematomas and peripheral nerve damage during surgery. These complications may lead to difficulties speaking or swallowing for several days. They are rare and most often disappear in a few days or weeks.

Carotid angioplasty

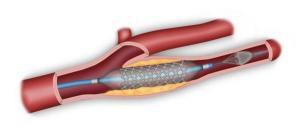

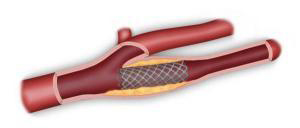

Endoluminal carotid angioplasty (via the inside of the artery) involves puncturing the femoral artery in the groin and inserting a dilating balloon loaded on a stent (metallic mesh) (Figure 9). According to the latest guidelines of the French National Authority for Health (HAS), this technique is not suitable for all patients.

Medical follow-up

After carotid surgery, regular follow-up by the vascular surgeon is required, along with Doppler ultrasound checks. Drugs continue to be taken. The risk of restenosis is very low, but warrants this monitoring.

Find out more…

Additional exams

When Doppler ultrasound reveals stenosis, the exam of choice is CT angiogram, with or without injection of contrast medium, to provide excellent images of the arterial stenosis, the parenchyma of the brain, and the Circle of Willis (an arterial system located at the base of the skull that links the various arteries supplying blood to the brain). In some cases, the stenosis has caused no clinical symptoms yet may have caused a silent stroke. MRI provides excellent data on the state of the parenchyma of the brain, but a less precise study of arterial lesions. Arteriography is rarely performed for carotid stenosis

Protecting the brain during surgery

To repair the artery, the surgeon must open it. Blood circulation to the arterial territory in question must therefore be interrupted. Most often, the brain hemisphere vascularized by the carotid undergoing surgery is supplied by the contralateral carotid and the vertebral arteries via the Circle of Willis, which creates redundancies between these various arteries at the base of the skull. Several techniques can be used to assess the proper cross-filling of the Circle of Willis: local anaesthetic to ensure proper brain function during the operation; taking residual pressure after clamping; monitoring the arterial backflow; and electroencephalograms. In some cases, this backup system is deficient, and the brain may not be able to withstand interrupted circulation. In these cases, the surgeon uses a carotid shunt (bypass tube) to maintain blood flow to the brain during the surgery.

Figure 10: Carotid shunt

Carotid angioplasty

In this technique, a catheter is inserted through the femoral artery into the carotid, equipped with an embolism filter to capture any atheromatous debris that might come loose during the procedure. A stent (metallic mesh) is then placed in the internal carotid, followed by a collapsed balloon which crushes the plaque against the artery wall once inflated. The risk of neurological complications is greater than with surgery. The French National Health Authority (www.has.fr) guidelines limit this procedure to patients presenting with surgical contra-indications or deemed medically unfit for surgery, as well as to complex pathologies such as stenosis following head and neck radiation or post-operative restenosis.